Fang reliquary baskets from southern Cameroon to Ogoowe valley in Gabon were generally crowned with statues but sometimes by heads alone. The heads were permanently attached to the reliquary baskets, since their function was above all to guard the family relics with their magical powers, protecting them from theft by sacrilegious curious women, children or strangers. Fernandez has suggested that the Ntumu style is the original form for all other Fang styles, regarding the ’heads on stalks’, with a heart-shaped face under a bulging forehead, as a type of proto-Ntumu style.

Items available for purchase

This statue is a fine copy of the “Black Venus” of the musee Dapper in Paris. The original sculpture was named so by Picasso and the French avant-garde artists. "she is the archetype of the style of the southern Fang Betsi…” The even-handed tranquility, composure, the capacity to hold opposites in balance, and the balance in proportion rather than in movement – these were the aesthetic qualities the Fang elders held in great esteem, as observed by James Fernandez. This fine female reliquary figure is seated, with a plinth that merges with her buttocks and thighs which, in the past, allowed it to be inserted into a reliquary receptacle

The three dimensions of this sculpture are beautifully balanced; its face, headdress, and hands are delicately modeled. In the Betsi style, the head is always large, imposing and majestic. This female figure holding an offering bowl is beautifully adorned with brass tacks in the coiffure's crest and in its protruding navel, and has wrist and ankle bracelets.

In typical Betsi style, this statue has balanced volumes: the upper and lower parts of the body are relatively equal, with a basket tied to the torso at the center of the configuration. The figure's seated posture and the plinth emerging from the buttocks resembles the original, suited to placement on the lid of the reliquary box, containing the sacred relics (skulls of venerated ancestors) for the ancestor cult.

According to Rivere "the cord serves to signify security and life, a notion reinforced by the tradition. Life is conceived as a 'cord of life'. In addition, cords are important because of their close identity with ideas of family and continuity". And to quote Gilli's words "on the cord of ancients, one weaves the new, meaning that thought and action is in conformity with the tradition of the ancestors".

The statue has a beautiful warm brown wood. Probably was used for unknown purpose.

This figure has the characteristic idealized Fang heart-shaped face with equally idealized and pronounced concavity. The coiffure is a helmet-wig (ekuma) with a band-like tress that extends across the forehead and falls from both sides of the head, and a thick central tress which reaches down the nape. The figure is in a seated posture, on a circular base, with her arms resting on her thighs. A. LaGamma, states, “Whether seated or standing, Fang figures often rest their hands on their thighs or abdomen in an expectant stance”. The only adornment added to her graceful simplicity is the carved bands around her upper arms.

This male reliquary figure (eyema-o-byeri) is highly characteristic of the Ntumu style. Despite its apparent simplicity of structure, it demonstrates a highly-skilled technique. It has an extremely elongated cylindrical torso – the most typical feature of the Ntumu style, and, according to L. Perrois' classification, it is in the 'longiforme' - The shoulders extend out, creating a rectilinear configuration, typical of the Ntumu style. The smooth arms are relatively frail. The thighs and calves are shortened, and a stalk that emerges from the buttocks enables the figure to attach to the reliquary basket and sit on the rim as the guardian of the sacred relics. According to L. Perrois, the exaggerated proportions were intended to give symbolic emphasis to important parts of the body, for example, the large head as the seat of wisdom and vitality, the protruding navel – a reminder of the link between humans and the dead ancestors from generation to generation,

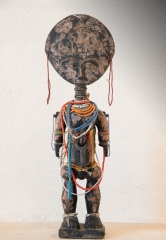

This Byeri articulated statue was probably used in a kind of puppet show, performed during the conclusion of the Malan initiation rites, of the ancestor cult. It was a comic show, intended primarily as a respite from the previous days, during which the participants engaged with death. According to L. Perrois, “Performing behind a small raffia screen, these wooden figures were manipulated by initiates seeking to show the new members of the brotherhood that the deceased - represented by the statues, were not really dead, but continue to participate in the life of their descendants in the village. Some statues were articulated, the arms and legs attached to the torso by cords”. The oval head has unusual elements. Especially striking are the head adornments, with a triangular woven headdress terminating in a tuft of feathers at the summit. According to L. Perrois: “The Fang took great care of their appearance at all times, more for symbolic and social reasons than specially aesthetic" . Another unusual element is the very stylish large rectangular ears, with large perforated triangular ear holes.

It is one of the most impressive figures in the corpus of the Fang reliquary sculptures.The Fang principles of "opposition and vitality" as defined by J. Fernandez are quite striking in this statue. The dense physical mass of the cylindrical torso and the strength of the supporting legs and buttocks, unparalleled in their monumentality, are contrasted with the extreme upper torso and relatively "weak" slender arms.This is balanced with a powerful impressive head with its massive mane of the coiffure, also unparalleled in its monumentality in the corpus of Fang sculptures. In addition, there is an andrognous element that one cannot ignore: a distinctive male organ,and small pedant flat breasts impying a feminine element. This enhances the impression of vitality through male-female opposition.

The feet suffer from hard erosion.

Statues portraying mother carrying a child are frequently to be found among Bena luluwa, linked to fertility cult especially the Bwanga bwa Cibola. This cult is the most popular rite observed by the tribe, for women who wish to mourn the death of a baby or young child, are Invited by the soothsayer to participate in the rite, to make the dead child reincarnate in its mother womb. Consequently many figures show pregnant women or mother and child. Moreover, as a child has to be persuaded not to abandon the family of his ancestors, many of these statues are naturally carved in realistic manner, resembling the ancestor images themselves. In addition, it is believed they protect pregnant woman and ensure successful childbirth, also watch over both mother and child during the weaning period, and guard against children's illness (Cornet 1999:157-8, 280).

Among the Luluwa Bena, the Bwanga bwa Cibola aided women, members in this fertility cult whose babies were stillborn or died in infancy. During pregnancy a woman is isolated for a specified period as imposed by the cult to commission a figure from a sculptor. The isolation ends, upon delivery of the figure. She has to keep the figure in a basket near her bed, and regularly rubs it with oil and a paste, brought out on nights with full moon, a symbol of fertility. This maternity figure is carved with detailed scarification, functions more symbolically rather aesthetically," as without a beautiful skin - one is considered evil". Thus the oily "healthy skin" of a figure must achieved by the woman to ensure the moral and physical integrity of her newborn child. (R. Sieber & R. A. Walker 1987:43).